Introduction to the Example Code

An empirical or computational research project only becomes a useful building block of science when all steps can be easily repeated and modified by others. This means that we should automate as much as possible, as opposed to pointing and clicking with a mouse. This code base aims to provide two stepping stones to assist you in achieving this goal:

Provide a sensible directory structure that saves you from a bunch of annoying steps and thoughts that need to be performed sooner or later when starting a new project

Facilitate the reproducibility of your research findings from the beginning to the end by letting the computer handle the dependency management

The first should lure you in quickly, the second convince you to stick to the tools in the long run—unless you are familiar with the programs already, you might think now that all of this is overkill and far more difficult than necessary. It is not. [although I am always happy to hear about easier alternatives]

The templates support a variety of programming languages already and are easily extended to cover any other. Everything is tied together by pytask, which is written in Python. You do not need to know Python to use these tools, though.

If you are a complete novice, you should read through the entire documents instead of jumping directly to the Getting Started section. First, let me expand on the reproducibility part.

The case for reproducibility

The credibility of (economic) research is undermined if erroneous results appear in respected journals. To quote McCullough and Vinod [MV03]:

Replication is the cornerstone of science. Research that cannot be replicated is not science, and cannot be trusted either as part of the profession’s accumulated body of knowledge or as a basis for policy. Authors may think they have written perfect code for their bug-free software package and correctly transcribed each data point, but readers cannot safely assume that these error-prone activities have been executed flawlessly until the authors’ efforts have been independently verified. A researcher who does not openly allow independent verification of his results puts those results in the same class as the results of a researcher who does share his data and code but whose results cannot be replicated: the class of results that cannot be verified, i.e., the class of results that cannot be trusted.

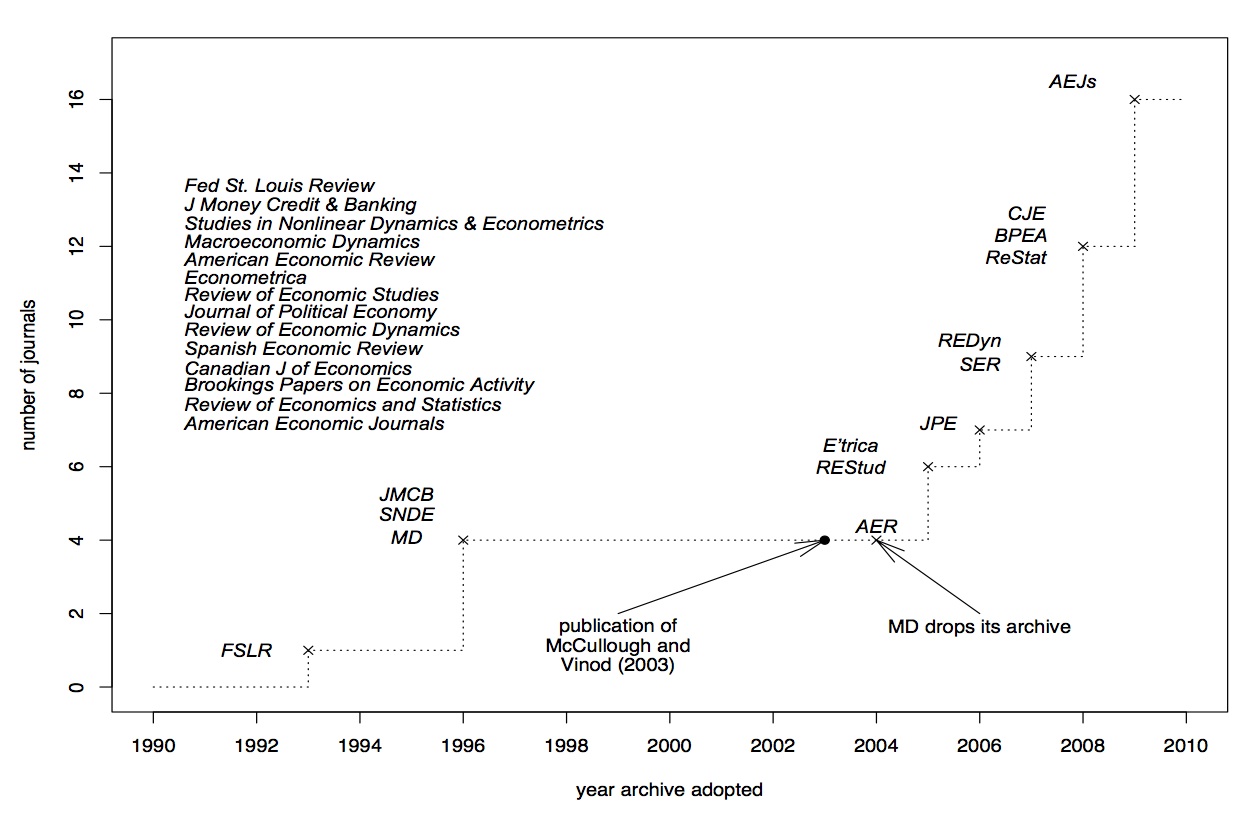

It is sad if not the substance, but controversies about the replicability of results make it to the first page of the Wall Street Journal [WallSJournal05], covering the exchange between Hoxby and Rothstein ([Hox00] – [Rot07a] – [Hox07] – [Rot07b]). There are some other well-known cases from top journals, see for example Levitt and McCrary ([Lev97] – [McC02] – [Lev02]) or the experiences reported in McCullough and Vinod [MV03]. The Reinhart and Rogoff controversy is another case in point, Google is your friend in case you do not remember it. Assuming that the incentives for replication are much smaller in lower-ranked journals, this is probably just the tip of the iceberg. As a consequence, many journals have implemented relatively strict replication policies, see this figure taken from [McC09]:

Economic Journals with Mandatory Data + Code Archives, Figure 1 in McCullough (2009)

Exchanges such as those above are a huge waste of time and resources. Why waste? Because it is almost costless to ensure reproducibility from the beginning of a project — much is gained by just following a handful of simple rules. They just have to be known. The earlier, the better. From my own experience, I can confirm that replication policies are enforced these days — and that it is rather painful to ensure ex-post that you can follow them. The number of journals implementing replication policies is likely to grow further — if you aim at publishing in any of them, you should seriously think about reproducibility from the beginning. And I did not even get started on research ethics…